My friend, Rob, is a hockey goalie who has a low neuromuscular activation. He doesn’t fidget or flinch. In the chaos of a hockey game, Rob looks like the 15th Incarnation of the Buddha of Serenity. His body stays in a still and focused state until a high-value target, for example a speeding projectile, approaches him within arm’s length. Without evincing any alarm or urgency, Rob’s hand snaps into motion, strikes his target, and disposes it. His body then returns to a state of calm focus.

By contrast, those of us with high neuromuscular engagement need our bodies in motion for our brains to fully activate.

For example, we routinely put groups of people into rooms for standardized exams like the SAT where they have to do high-level cognitive work while sitting still. There’s durable research conducted across cultures showing if you give half the group gum to chew during the exam, they’ll do measurably better than the control group. Just the modest amount of muscular activity generated by working our jaws generates a powerful boost to our cognition.

Most of us need our bodies in motion for our brains to reach their highest level of activation. Traditional cultures have understood this. That’s why we have beads and wheels, yoga positions, davening, kneeling, prostrations and other physical aids to prayer and meditation. We have traditionally shared a common understanding that our bodies need to be engaged to support our attention and focus. Muscle movement gets associated with certain memories in the same way odors or colors do, and assist in the retrieval. Before the invention of the typewriter, many office workers stood at their desks. Ebenezer Scrooge and Bob Cratchit kept their accounts at stand-up desks. Even until late in the 20th century, we stood and bent to maintain our files, walked, or maybe even raced, to put a note on someone’s desk or inbox.

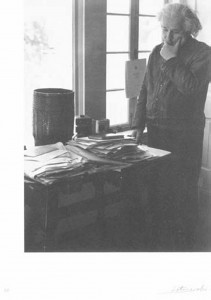

Dr. Einstein standing to think (photo credit: Lotte Jacobi University of New Hampshire)

By contrast, for nearly all of us, when we sit, our ability to remember, to process information, in short to think, decreases. The higher up you are in the mover scale, the more cognitive functioning you lose by sitting.